廣受外界期待、由 AppWorks (之初加速器) 主辦的 AppWorks Demo Day #23 + Wistron Demo Day #1,在今日 (12/15) 於台北熱鬧登場,有 16 支來自 AppWorks Accelerator #23、5 支來自 Wistron Accelerator #1,共 21 支新創團隊輪番登場,展現過去 3 個多月的加速成果。

11 年來每年舉辦兩次的 AppWorks Demo Day,早已是大東南亞 (東協 + 台灣) 新創圈的盛事之一。舉辦的主要目的,在於為當期 AppWorks Accelerator / Wistron Accelerator 團隊提供舞台,並促進新創社群的國際交流、投資、商務媒合,以及創造更多的可能性。受到疫情影響,本次 Demo Day 改為邀請制,進行入場人數控管,AppWorks 總共邀請了約 500 位來自創投、企業、新創以及其他相關單位的代表蒞臨,持續為大東南亞地區的創業生態系挹注能量、創造蓬勃發展。

AppWorks 自 2010 年啟動第一屆創業加速器以來,就持續積極結合各方資源,累積更大的影響力,為創業者打造最佳的協助平台。AppWorks 董事長暨合夥人林之晨指出:「AppWorks 的長期目標一直都沒有改變,我們希望協助優秀的創業者,掌握典範轉移所帶來的顛覆機會,最大化他們對台灣以及整個大東南亞區的影響。在這個階段,我們最看好三大板塊位移,也就是 ABS – AI、Blockchain、Southeast Asia。此外,在過去兩年,我們也看到 NFT 成為另一個快速崛起的典範轉移。NFT 是 Blockchain 技術中,快速成長的巨型應用,為數位資產的擁有權帶來突破性改變,並成為實現 Web3 世界的關鍵基礎。正因為 NFT 帶來如此廣泛且重要的影響力,因此,我們相信值得將它自 Blockchain 領域獨立出來看待,就好像電子商務之於 Internet 的關係。」

在結合各方資源下,本屆 Demo Day 也呈現截然不同的風貌,相較於過往,本次 Demo Day,共有三大堪稱里程碑的亮點:

1. AppWorks Accelerator: 新創成熟度高、策略結盟區塊鏈 Flow

自 AW#23 起,AppWorks Accelerator 正式與區塊鏈一線公鏈 Flow 策略結盟,共同推動區塊鏈生態系。AppWorks 自從 2019 年投資 Flow 以來,就一直與 Flow 公鏈、同時也是 CryptoKitties 與 NBA Top Shot 開發團隊的 Dapper Labs 保持非常密切的合作,有計畫地持續推動建構在 Flow 公鏈上的各式 NFT 應用與生態系。從遊戲與娛樂起步,在基礎建設日趨成熟下, Flow 正成為一個蓬勃發展的生態系。

Flow 為進駐 AppWorks Accelerator 的新創,提供專屬的服務與資源。包括 Flow 團隊在技術、行銷、社群和產品方面的專屬支持;由 AppWorks 安排與 Flow 團隊的 Office Hours;共享 Flow 的教育資源、以及其它 Flow 區塊鏈專案的寶貴經驗;優秀的開發專案,有機會獲得 Flow 與其他夥伴的投資;獲得 FLOW Token 贊助機會,將產品發佈於 Flow 主網,加速初期獲客。

除了一線公鏈的合作外,AppWorks Accelerator 長期聚焦在 ABS 三大主題,並持續看好 NFT 的發展。從本屆 Demo Day 登場的團隊身上,可看到 AppWorks Accelerator 持續吸引越來越多國際優秀創業團隊進駐,繼續引領大東南亞地區創業生態前進。在這些明日之星中,有來自台灣、新加坡、香港、美國與英國的團隊,也有不少連續創業者,曾擁有成功出場的經驗,整體不論在創業經驗、產品或服務、商業模式等面向上,都展現出更加成熟、更加多元的特色。

例如,開發 Web3 去中心化照片網路,使數位媒體資產可被追溯與驗證的 Numbers,在 8 月創下百萬 API Access、用戶來自超過 90 個國家,並在近期完成 600 萬美元的私募種子輪募資,投資人包括開發出 Filecoin 的 Protocol Labs、交易所 Binance、為新創提供技術平台和募資框架的 MakerDAO,以及 YouTube 共同創辦人陳士駿、Twitch 共同創辦人林士斌。

來自新加坡的網紅行銷平台 Partipost,為品牌媒合社群推廣的網紅與內容創作者。目前已將版圖拓展至台灣、新加坡、印尼、馬來西亞、菲律賓等五個市場,與近 65 萬名網紅、創作者,以及超過 2,000 個品牌展開合作,並在今年完成 500 萬美元 A 輪融資,投資人包括 Quest Ventures、SPH Ventures 等。

針對亞洲女性開發健身 App 的 Nuli,平台上已打造超過 400 種健身課程,累積近 1.4 萬名付費訂閱用戶,今年以來的成長率達 126%,在所有付費用戶中,接近一半選擇使用年度訂閱方案,展現強大的用戶黏著度。

本次 16 支登場的 AppWorks Accelerator #23 新創團隊,簡介如下:

1. Numbers: 去中心化照片網路,在數位媒體領域創造社群、價值與信任。

2. DeFITs: 由 DeFi 模式驅動的加密貨幣資產管理平台。

3. ROJU: 多合一跳繩健身 App。

4. Partipost: 網紅行銷平台。

5. Nuli: 針對亞洲女性開發的健身 App。

6. GranDen: LBS / O2O 社交遊戲 Metaverse。

7. DimOrder: 餐廳 POS 系統。

8. Hooky: 數位資產管理平台。

9. Voutyque: 為亞洲獨立品牌打造的社群電商平台。

10. foptics: D2C 眼鏡品牌 。

11. Cardbo: AI 驅動的數位支付管理工具。

12. Toko: 英文口語 AI 練習 App。

13. Gather Stars: 整合 email、簡訊、語音的溝通協作 AI 平台。

14. Dress As: 800 萬追蹤者的時尚圖片分享社群平台。

15. AnyoneLab: 創作者商務管理 SaaS 服務。

16. ESEN: 結合知識平台與線下診所的家庭醫學 O2O 平台。

2. Wistron Accelerator: 緯創集團各事業體協助加速

繼 AW#23 共 16 支新創團隊登場後,緊接著是 Wistron Accelerator #1 共 5 支新創團隊登場。緯創身為全球 ICT 產業的領導廠商之一,近幾年在強化研發、提升技術創新、多元化產品開發、建立新技術產業鏈以及創新平台、前瞻性投資等策略上,展現出傑出成果,也使得 Wistron Accelerator 不僅廣受外界關注,更成為台灣大企業與新創策略合作的指標。

緯創與 AppWorks 從 2014 年開始合作,是 AppWorks Fund II、Fund III 的主要股東之一,之後也陸續投資了 MoBagel (AW#16)、ANIWARE (AW#17) ,與 LucidPix (AW#18) 等自 AppWorks Accelerator 畢業的新創校友,雙方有長期的策略合作關係與默契,並在今年 9 月首度啓動緯創垂直加速器,由 AppWorks 提供營運等核心業務。

緯創資通董事長林憲銘指出:「Demo Day 不是加速的結束,而是另一個階段的開始。與新創合作、互相交流與學習,結合雙方的優勢,是我們長期的策略目標,因此,我們願意用更長的時間去等待開花結果、產生綜效。」

Wistron Accelerator 能順利啟動、快速展現成果,關鍵在於獲得緯創集團各事業體的支持 (Endorse)。因此,Wistron Accelerator 最大特色,就是由緯創集團各事業體最高負責人擔任 Mentors,進行獨家合作 PoC,獲選的新創,可直接與緯創各事業群高階主管討論,在合作主題和方向、商品化、規模化等面向上,都能由 Top-down 建立長期的策略與目標,加速並放大成果。

例如,專注於提供 AI 身分認證的 AuthMe,此次與緯創展開 KYC 應用合作,共同開發遠距醫療解決方案,在病患登入時進行身分辨識。以軟硬體整合,開發各式物聯網設備的 BeeInventor,提供智慧營造解決方案,在與緯創進行 PoC 後,並進一步將合作拓展至旗下緯謙科技、緯昌科技。正在招募中的 Wistron Accelerator #2,緯創集團旗下的緯育、緯創醫學科技、啟碁科技也將加入與新創合作,協助加速的行列。

本次 5 支登場的 Wistron Accelerator #1 新創團隊,簡介如下:

1. AuthMe: 專攻身分認證及詐欺防範的 AI 解決方案。

2. BeeInventor: 為建築工地提供 AI 解決方案。

3. BSOS Tech: 以區塊鏈技術提供供應鏈金融服務。

4. Poseidon Network: 去中心化雲端聚合儲存方案。

5. 3drens: 大數據驅動的 IoT 車輛管理平台。

3. LINE Bank X AuthMe 對談:在 AppWorks Demo Day 之後展開的策略合作

本次 Demo Day 另一個亮點,則是首度進行大企業與新創對談,邀請純網銀 LINE Bank 總經理黃以孟,與台灣領先的數位身分驗證解決方案 AuthMe (AW#18) 共同創辦人暨執行長李紀廣,共同分享合作的經驗。

在 2019 年 6 月登場的 AppWorks Demo Day #18,黃以孟在聽完李紀廣上台 Pitch 後,對 AuthMe 的技術與應用非常感興趣,在活動後的交流時間,親自與 LINE Bank 的團隊,前往 AuthMe 的攤位與李紀廣交流,並在隨後很快地敲定了雙方團隊的正式會議,也因此開展了後續的合作,AuthMe 因此成為 LINE Bank 在 KYC 的技術夥伴。

從大企業的角度,黃以孟指出:「純網銀背負了外界極大的期待,透過與 AuthMe 的合作,讓我們得以快速掌握創新科技,進而為客戶提供更高品質、更高效率的金融服務。LINE Bank 將新創夥伴看作是企業研發中心的延伸,未來將持續往 Banking 4.0 升級里程上,尋找適合的合作機會。」從新創的角度,李紀廣則指出:「金融業必須符合最高等級的資安與法遵要求,經過與 LINE Bank 的合作和檢驗後,讓我們的技術和解決方案,得以更順利推廣至其他產業和領域。」

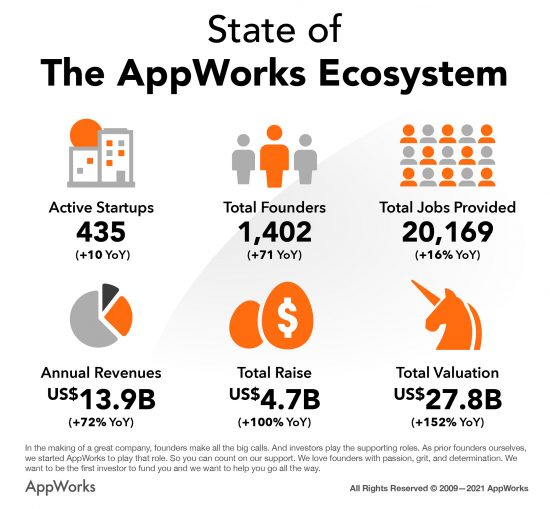

AppWorks 生態系持續加速成長

至今已來到第 23 屆的 AppWorks Accelerator,飛輪正不斷加速轉動,整體生態系持續展現出超越過往的成長速度。在累計募資金額、全體總價值都繳出成長 100% 以上的佳績,全體創造就業數更突破 2 萬的重要里程碑,代表為大東南亞地區的經濟發展帶來實質貢獻。具體成績包括:活躍新創累積至 435 家、共 1,402 位創業者,所有新創的加總年營業額來到 139 億美元 (約為 3,773 億新台幣),較去年同期成長 72%,全體提供就業數 20,169 位,年增 16%,生態系累積募資金額來到 47 億美元 (約為 1,304 億新台幣),年增率高達 100%,總價值達到 278 億美元 (約為 7,718 億新台幣),較去年此時大幅增加 152%。

同時,區塊鏈產業的崛起速度遠勝以往,AppWorks Accelerator 自從 2018 年開始積極招募來自區塊鏈領域的新創,目前,整體生態系已有超過六分之一,共 75 家活躍新創、141 位創業者來自區塊鏈領域。

林之晨指出:「AppWorks 將持續推動 AppWorks 生態系、所有新創校友與各種類型的企業與機構合作,一起掌握 AI、Blockchain、Southeast Asia 三大典範轉移所帶來的各種機會,推動各式數位轉型、為大東南亞數位經濟圈創造更強大的影響力。」

#關於 AppWorks 之初加速器集團

2009 年成立,由「創業者」為「創業者」設立的加速器,以及基於加速器發展的新創社群與創投機構,致力在大東南亞地區協助下世代的創業者,抓住數位革命的成長機會。正如同 Mobile Internet 帶來了巨變,我們相信 ABS – AI、Blockchain 與 Southeast Asia 是今日的三大典範轉移。我們認為,創造一個偉大事業的過程中,團隊是主角,而投資人則是配角,我們專注扮演配角,從種子時期開始支持有想法的團隊,一路陪著他們打造區域級、世界級的偉大企業。AppWorks 目前共提供 Accelerator、Funds 與 School 等三項主要服務。

更多資訊:appworks.tw

#關於 AppWorks Accelerator 之初加速器

2010 年成立,每半年嚴選本區域最具潛力的新創團隊進駐。輔導新創團隊尋找 Product-Market Fit、幫助成長期團隊建立 Sustainable / Scalable Business Models。成立以來,從 AppWorks Accelerator 畢業的活躍新創已達 435 家、1,402 位創業者。過去一年來,AppWorks Ecosystem 大幅成長,所有企業加總營業額達 139 億美元,年增 72%,提供就業數 20,169 位,年增 16%;生態系累積募資金額達 47 億美元,年增 100%,總價值則達到 278 億美元,年成長達 152%。

#關於 AppWorks Funds 之初創投基金

AppWorks 管理三支創投基金共 2.12 億美元,我們與認同我們理念的投資人合作,其中包括在科技製造、金融、媒體等業界領先的龍頭企業。我們每年進行 20 個投資案,目前為止已持股超過 70 家新創,其中許多在其垂直居於領先地位,如:Lalamove、Dapper Labs / Flow、Animoca Brands、91APP、Carousell、ShopBack、Tiki、17LIVE、KKday 等。此外,並已有 5 個 IPO 案 (Uber、隆中網絡、創業家兄弟、松果購物、91APP)、3 個 IEO 案,以及 1 隻百角獸 ( Hectocorn)、2 隻十角獸 (Decacorn) 與 4 隻獨角獸 (Unicorn) 。

#關於 AppWorks School 之初學校

AppWorks School 成立於 2016 年,致力協助渴望投身數位、網路與電商產業的人才,提供免費、實作、高效、與業界結合的紮實培訓計畫。成立至今,已畢業 352 位學員,其中 90% 成功投身網路界,在 momo、91APP、KKBOX、Line TV、WeMo Scooter、Line Taxi、Hahow、VoiceTube、OmniChat 與 Gogoro 等知名新創與科技公司擔任軟體工程師。現經營有 iOS、Android、Front-End、Back-End 與 Data Engineering 等轉職專班以及軟體工程師進修班。

更多資訊:school.appworks.tw

【歡迎所有NFT、Blockchain / DeFi、AI / IoT 以及目標 Southeast Asia 的創業者,加入專為你們服務的 AppWorks Accelerator】